By Brian D’Ambrosio

One of Josef Skye Tornick’s photographs is of an old woman who sold candles and religious objects out of a makeshift shrine in her Santa Fe home many years ago. She holds a photo of herself as a young girl, any hint of similarity almost imperceptible. Tornick doesn’t remember the woman’s name. Both the subject and the setting are long gone.

Then there’s the photo of an old train station in Ancho, NM, where a couple once sold antiques from dusty display cases. It was called the “House of Old Things.” Today, the site is wholly abandoned, rotting.

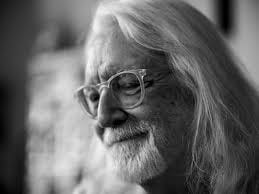

Both are typical of Tornick’s photography, which is largely preoccupied with vanishing places and people that came with the dust and blew away with the wind. Over the years, the 75-year-old has experimented with many forms of visual expression, from the decorative and fine art images that appeal to the tourists, to documentary-style photos taken chiefly in New Mexico, Ireland, England, and Scotland. It is in these places where he is drawn to ruins, the worn-out, the time-ravaged.

“Gallery owners will tell you that documentary does not sell and people don’t buy those images to put on their wall,” Tornick said. “But documentary is a fluid category – landscape, or old buildings, or a canyon with a light coming down. To me, documentary photography could be a souvenir of New Mexico.”

Tornick, who lives in Santa Fe, is at his best when he is trying to document subjects that are about to disappear, like the twilight essence of a wrinkled Mexican man in Magdalene or a gnarled roadside sign advertising “Pinto Bean Capital of the World.”

Vanishing Façades, Lost Legends

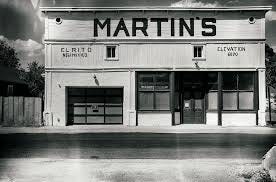

One of Tornick’s most popular photographs is of the Santo Domingo Trading Post in glorious decline, before its façade was neatly remodeled and repainted.

“I was taking the train to Albuquerque and looked out the window and saw an old complex of buildings go by quickly,” Tornick said. “It looked like authentic New Mexico. I went back with my car and looked around near Santo Domingo Pueblo and found something representative of the old New Mexico that had vanished. I located some original magazine articles of the old trading post in the heyday in the 1940s, with the old cars out in front. There had been a fire that gutted it, except for the remnants of the old sign.”

Years later, he returned to find that the front wall of the Santo Domingo Trading Post had been restored, replete with an ultra-modern paint job, though its rear remained open and exposed. Tornick captured the shop’s deterioration at the right time, and the photo has ignited many conversations, legends and memories.

“Over the years at art shows, I’ve met several people who remembered their grandmother taking them into the store to buy moccasins, or who have shared an anecdote like that. Someone came to the booth once and said they used to work in that store when they were little.”

There have been other parallel experiences in Tornick’s travels, images taken along the dusty roads near the Mexican border, through vanishing towns like Duran. There was a long, copper sign advertising the town of Ancho that he discovered after many miles of light gallivanting. The sign was washed out, weary, and inherently appealing. The next time that he returned it was not there.

A photo taken in Silver City about 10 years ago is of an abandoned coffee shop with an art deco motif. It was once part of the Murray Hotel, built in the late 1930s and operated by one of the area’s few Chinese women. Apparently, she was famous for her key lime pie. Tornick snagged several shots of the words “coffee shop” emblazoned across the pale blue exterior. Though the hotel was vacant and many of the windows were broken, the text held vivid memories, the evidence of a previous narrative. Years later, Tornick was disheartened to find that the building had been restored, the “coffee shop” lettering invisible, and its earlier, surrounding colors remade tan and brown.

Return to First Love

Born in Brooklyn, NY, Tornick’s talent as a photographer is almost as compelling as his trajectory as an artist.

“I took it as a child and was self-taught in high school,” he said. “I would get magazines from the library about photography. I developed photos in trays in the sink in the darkroom in the basement. My parents took me to Mexico, and I had three rolls of film and shot a Mexican woman making tortillas when I was 14, and several other images. Three rolls for the whole summer. Ninety pictures.”

Tornick enrolled in a single photography course in college, but then abandoned the practice for 30-plus years.

In 2003, Tornick found himself in an extended period of self-interrogation. He had worked hard to obtain a master’s degree in counseling, but he couldn’t find suitable employment. For two years, he kept asking himself what he should do with his life.

“There was the quiet voice of spirit that reminded me that I liked photography as a child,” Tornick said. “The idea grew and got stronger in my head. My inner life and art had fused and there was no more conflict.”

Subsequently, Tornick walked in the footsteps of Paul Strand (1890-1976), who published a series of photography books that documented the traces of vanishing cultures, most notably on the edge of society in the Hebrides on the West Coast of Scotland. Tornick even sat down with some of Strand’s original subjects and talked with their relatives and friends, all while attempting to replicate the poses and positions of the iconic photographer’s finest shots. He was on the remote islands for six and half weeks, shooting 160 rolls of film. It proved to him that at age 54 he could make photography his career.

Today, Tornick is embracing the pleasurable anonymity of the photographer, the sly hidden hand of the documentarian.

“My photographs are straightforward,” he said. “There is no interpretation, there is no point of view, and there is no slant. You are seeing things how they are, and the photographer is absent. That is a lifetime’s challenge.”

Another great and sincere piece