American Eccentrics: Ralph Teetor

Despite Obstacles, Automotive Inventor Possessed Clear Vision

By Brian D’Ambrosio

“The only real creative factor is the ability to think: You don’t create with your eyes.”

These are the words of Ralph Teetor, the Indiana born engineer and inventor who lived a life of utter genius despite his being blinded at a young age.

Long serving as the president and head of the family run corporation that he was a part of since childhood, Teetor used his thinking abilities to develop a number of manufacturing tools, gadgets and procedures adopted by the automobile and aviation industries, including piston rings for engines and a process for balancing turbine rotors in destroyers during World War I. But possibly his most far-reaching brainchild was something called the “Speedostat, “a driving aid to the motorist who wishes to maintain a constant speed,” as he described it, now a standard feature on most vehicles known as “Cruise Control.”

The Route is Set

Born August 17, 1890, in the small village of Hagerstown, Indiana, close to the Ohio State Line, Ralph R. Teeter (the family name would not be altered to “Teetor” until he was well into adulthood) lived a typical, content childhood before an accident at the age of five changed his life forever. “While playing with a knife he in some way thrust the blade into one of his eyes cutting the ball badly,” noted The Hagerstown Exponent on March 25, 1896. In May 1896, the wounded eye worsened and at the doctor’s insistence an operation was performed in Indianapolis to remove the ball of the distressed eye. In the subsequent weeks, it seemed as if Ralph’s good eye was healing properly and that his prospects of retaining normal eyesight were quite favorable. However, The Hagerstown Exponent on October 7, 1896, reported that “Little Ralph Teeter is again threatened with total blindness.”

The boy suffered with an injured eye that occasionally showed signs of improvement for more than a year. But by the end of 1897, his vision continued to weaken and by the time that he was seven years old his sight was practically gone. (Undiagnosed at the time, the exceedingly rare condition called sympathetic opthalmia caused the injured eye to produce inflammation and ultimately blindness in the second eye.)

According to Marjorie Teetor Meyer’s book about her father, One Man’s Vision, The Life of Automotive Pioneer Ralph R. Teetor, the Teeter family adjusted to the loss of Ralph’s vision with dignity and courage and developed their own unique system of coping with the harrowing chain of events. Kate and John Teeter, Ralph’s parents, would not allow their son to perceive the world in self-pitying or self-defeating terms.

“Essentially they lived their lives as if Ralph could see normally. The problem was never mentioned unless circumstances made it absolutely necessary.”

His parents inculcated in him the conviction that he could lead as normal and happy a life as anyone and achieve whatever goals he wished to pursue. His mother read to him books and stories about creative, determined types, the engineering and intelligent exploits of men such as DeWitt Clinton, Eli Whitney, Benjamin Franklin, and especially Thomas Edison. Something about these titans and their shared traits of perseverance, creativity, and innovation inspired and elevated the young boy. Ralph also had the benefit of being raised in an incredibly intellectual environment: John and his brother Charlie Teeter were avid tinkerers and started their own industrial corporation, incorporating the Railway Cycle Manufacturing Company on February 16, 1895.

Ralph grew up around the sounds and smells of the factory, and he was never discouraged from learning more about the vagaries of the mechanical world or asking questions about what he heard of felt or indulging in his curiosity.

“Ralph progressed from learning how to use hand tools to running all the machines, lathes, milling machines, grinders, and drills at the factory,” according to One Man’s Vision. “The uncles taught him how to plan, measure, create, and polish to make something perfect in wood or metal.”

By age ten, Ralph was spending ample time familiarizing himself with the machines and tools that his father installed in the workshop and shed that he built onto the rear of the house.

By the time that he was age 12, he and his second cousin Dan built an automobile in his workshop, and the December 21, 1902 edition of The New York Herald extolled the whiz prodigy as an example of achievement. The November 19, 1902 issue of The Cincinnati Enquirer labeled Ralph as “a story of success” and described the vehicle, which was boosted by “a discarded gasoline engine” in detail, including “the steering device and fuel and water tanks on the machine” that “were designed and constructed by himself.”

No reference in any of the newspaper reports was made to his blindness, and it’s possible that the reporters weren’t even aware of or alerted to Ralph’s shortcoming.

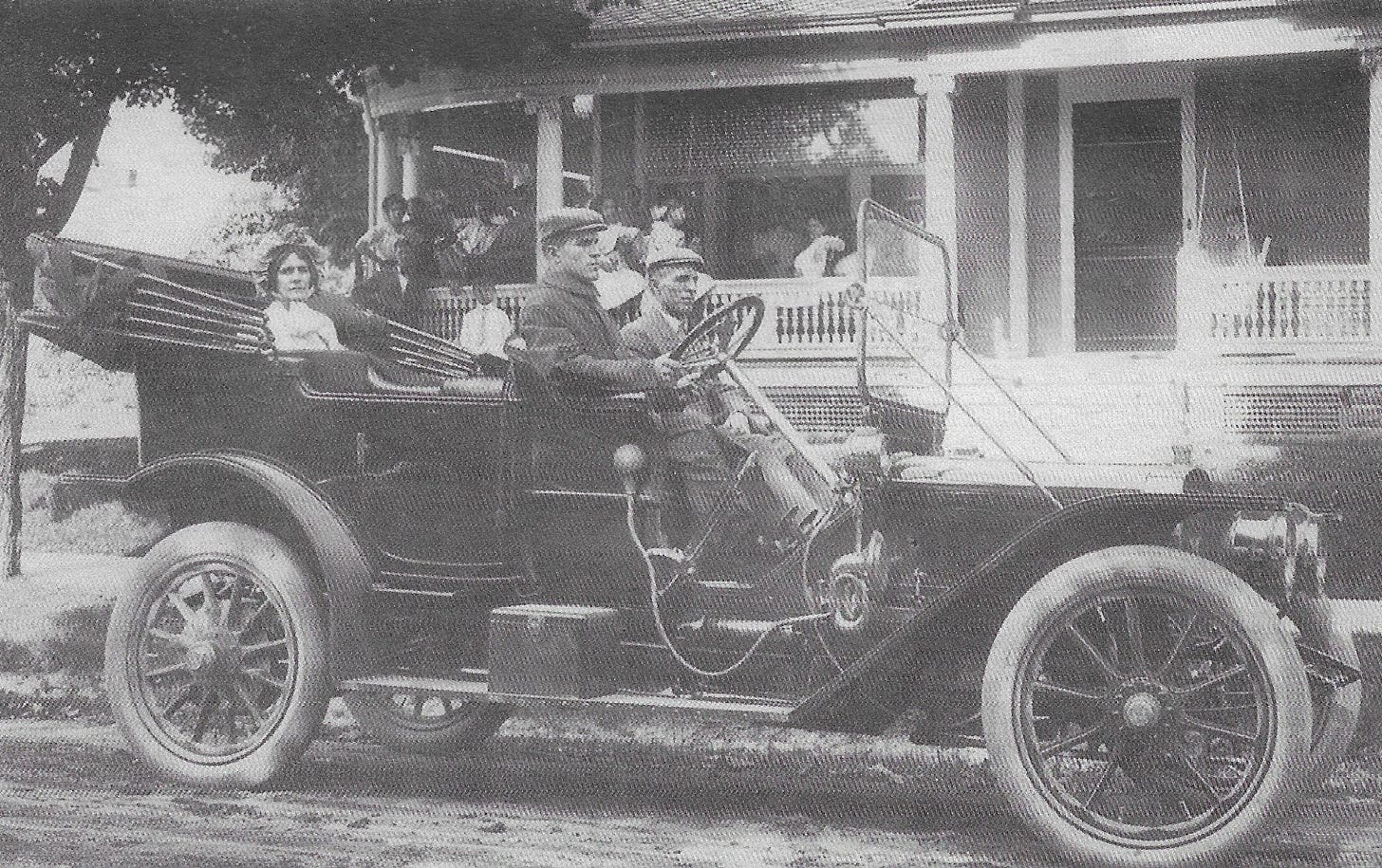

Ralph Teeter graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Pennsylvania on June 19, 1912, in Philadelphia. There is a well-circulated image of Ralph and his parents, in front of his family home, sitting in the American Underslung automobile gifted to him by his father for his college graduation, his countenance serious, gaze focused, hands fitted to the lower portion of the steering wheel.

Trail of an Automotive Pioneer

In 1912, the business that Ralph’s father and uncle founded was renamed the Light Inspection Car Company and, adjusting to the changing realities of transportation, began building engines for the McFarlan, “one of the finer cars of its time, each unit individually built with many custom features,” with Ralph assembling small chassis.

In 1913 the board of directors decided to change the name of the company to Teetor-Hartley Motor Company. (A man named Charles Hartley invested in the initial formation of the company in 1895). The modification in the company name reflected the wish of some of the Teetor descendants to correct the frequent misspelling of the family name. Around that time, Ralph began to use the “Teetor” spelling.

In 1924, Teetor received a patent for a hydraulic gear shift for automobiles. As the automobile increased in popularity and prevalence, the demand for replacement and service parts grew too, and the company embraced the opportunity to develop and market a niche necessity. The more cars and paved roads, the more mileage logged, and the more piston rings exhausted. Someone in the company began calling the piston rings “Perfect Circles” and the name stuck, so much so that Perfect Circle became the company name in 1926.

On February 21, 1933, Ralph, an avid fisherman, received a patent for a new type of fishing pole handle. He continued to improve on his patent but was never able to break into the recreational sports market with the same success that he had with automobiles and mechanics.

In 1937, Charles Teetor, Ralph’s uncle, died while serving as president of the company; two years later, John Teetor, Ralph’s father, died at age 79. Ralph’s role in the company deepened and his participation in the automotive engineering world seemed to widen, including his role as president of the Society of Automotive Engineers. A pamphlet from an event held on March 24, 1936 boasts of a reception, dinner and entertainment, and the quote “Keeping the Automobile Industry Young,” is to be found above Ralph Teetor’s name.

On July 12, 1945, Teetor addressed 200 blind veterans of World War II at the Valley Forge General Hospital, and excerpts were recorded in a press release distributed by the public relations office of the Army. “Remember, you are not handicapped so long as you can think logistically,” Teetor was quoted as saying. “You will be handicapped only if you are slovenly in your thinking.”

“Speedostat” Patent

During World War II, the US government in an attempt to conserve gasoline and prolong rubber tires imposed a national speed limit of thirty-five miles per hour. Drivers found it difficult to stick to such a slow speed. Teetor concluded that most drivers were speeding up and slowing down, wasting gasoline, and that they were also endangering themselves and their passengers constantly shifting their attention from the road to the speedometer. Ralph envisioned a speed control device that could be set to the driver’s chosen speed. He went back to his basement workshop and tinkered with the project. In the spring of 1945, he filed for the first patent on his device. It took several years for Teetor to develop a credible working model, and on the suggestion of his wife, Nellie, he re-named his invention the “Speedostat.”

According to One Man’s Vision:

“By late 1957 Ford, Chevrolet and Chrysler were all testing the Speedostat. Chrysler, however, was the first to commit, offering it on their 1958 Imperial, New Yorker and Windsor models. It proved to be so popular that by the end of 1958 they were offering it on their entire line of new cars.”

Chrysler began to market Teetor’s device as the “Auto Pilot” and soon after Cadillac started to offer the Speedostat as optional equipment of all its new vehicles, electing to call it “Cruise Control.”

In 1963, Perfect Circle became a wholly-owned subsidiary of Dana Corporation, and at age 73, Ralph Teetor retired. In 1995, one hundred years after the Railway Cycle Manufacturing Company was started, its last factory door in Hagerstown, Indiana, closed.

Ralph Teetor died on February 15, 1982, though shortly before then he was asked by another of the Speedostat’s engineers, Jack Swoveland, about the legacy of his greatest industrial invention.

“Look at all the lives it has touched, the jobs it has provided, not only at Perfect Circle, but suppliers, mechanics, and others, and the pleasure and added safety it has brought to so many drivers. That gives me a lot of satisfaction.”

Brian D’Ambrosio is at work on a book about “American Eccentrics.”